The future of chronic care management: a healthcare revolution

23 May, 2023

The tech of e-commerce giants in the palm of your hands

14 August, 2023Leave no plastic behind: creating a true circular economy

3 July, 2023

Back in 2021, the new paper packaging for a hugely popular beauty brand’s green tea seed serum caused a fracas on the Internet.

As it turned out, it may have been a well-intentioned marketing ploy gone horribly wrong. The brand apologised, and it all blew over. For our purposes, though, the whole incident is a great reminder that despite all the real concerns about the ecological and health impact of plastic pollution, phasing out plastic is very, very, hard. Plastic is basically a miracle material. It’s light to transport, cheap to buy, permeable when you want it to be and impermeable when you don’t. And, of course, it’s durable.

The real problem with plastic is that there is no good solution for disposal. There is a reason why more than 90% of plastic in the world is never recycled today. Switching out plastic for alternative materials often result in a higher carbon footprint and higher resource intensity. Asking most people to reduce their plastic consumption only works until their conscience runs up against their desire for convenience. And that’s why we invested in Cleanhub, a company founded in 2020 by Joel Tasche, Louis Pfitzner and Florin Dinga that is using fintech product development principles to prevent 50% of new ocean plastic by 2030.

It’s hard to think of a sector with stronger tailwinds than plastic pollution:

- There’s consumer pressure. Carbon may be a bigger problem for climate change, but greenhouse gases are invisible and carbon emission calculations can get downright arcane. Plastic is tangible and unavoidable – whether it’s the beach you visited on your last surfing holiday, the trash can next to your desk, or the microplastics-riddled dover sole you ate for lunch. Carbon is theoretical, but plastic is personal

- There’s legislative pressure. 50+ countries to date have established some form of extended producer responsibility (EPR) laws; another 40+ countries have EPR laws under development. The EU is proposing new EU-wide regulations that would mandate minimum 30% recycled content in plastic packaging by 2030 (and 50-65% by 2040.)

- The combination of consumer and legislative pressure means that companies have to do something about it. Companies (like Unilever, P&G, and Henkel) representing approximately 20% of global plastic use annually are signatories to the Global Commitment to reduce plastic consumption. Some have set public goals for post-consumer recycled content in their packaging. The word “plastic” appeared 76 times in Coca-Cola’s most recent annual report; it appeared more than 100 times in Unilever’s. It’s a priority.

But what does “doing something about it” mean? In this article, we’ll talk about:

- Why recycling rates are so low today, and why it’s so hard to do something about it

- What Cleanhub does today: The power of peer pressure

- What Cleanhub wants to do tomorrow: Asset-light waste plastic supply chains (powered by fintech)

- Some important technology tailwinds: A brief foray into plastic recycling

- The counter-case: what are the risks?

- Some final thoughts

Why Recycling Plastic Is So Hard

The simplest reason is that plastic needs to be collected in order to be recycled. That may seem obvious, but it’s a huge problem in regions where waste management infrastructure is severely lacking. The U.S. and Europe directly account for only 5% of the world’s plastic leakage into the oceans (vs. ~25% of global plastic consumption). It’s the developing world – Asia, West Africa, South America – where 80% of river-to-ocean plastic comes from.

Second, not all plastic can be recycled. Everyone feels guilty about disposable water bottles, but PET is actually a great source of value in the plastic recycling stream. In emerging markets, this is the material that waste managers are willing to collect, because they know they can make a margin selling it on. The stuff that is flowing into the oceans is what’s known as multi-layer plastics: frozen food bags, chip bags, granola bar wrappers, which recycling plants won’t accept and won’t pay for. (Plastic grocery bags are recyclable, but they tend to clog up processes at recycling plants and so are accepted in only very few places.)

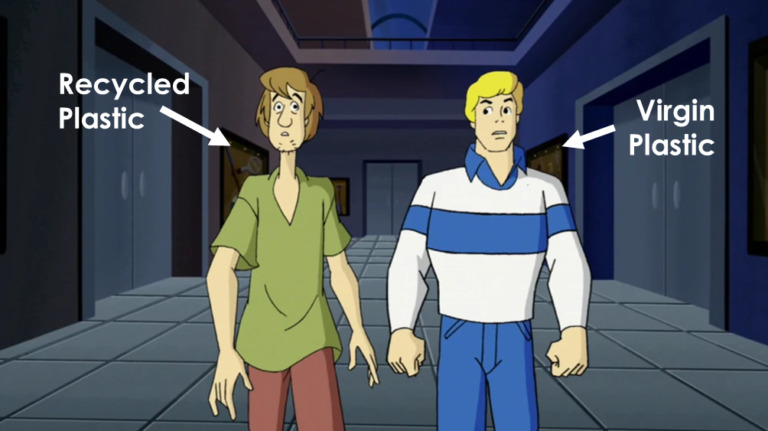

The third reason, and the most intractable, is that recycled plastic has to compete with virgin plastic in the packaging materials marketplace. And virgin plastic has a 50+ year head start on recycled plastic. Like everything else in our industrialised world, the virgin plastic supply chain has been scaled and enhanced and optimised to the nth degree and beyond. Post-consumer recycled plastic just can’t compete. In Scooby-Doo terms, virgin plastic is Fred. Recycled plastic is Shaggy. And Shaggy doesn’t fit into a modern, efficient, industrial supply chain.

It’s hard to imagine but it’s true – in a world awash with plastic waste, there’s a massive supply shortage of high quality recycled plastic that can compete with virgin material. And demand for recycled plastic is only going up.

What Cleanhub Does Today: The Power of Peer Pressure

Cleanhub’s business today is simple: it sells plastic credits to Western consumer brands, and uses the money to fund the collection of nonrecyclable plastic waste from households in emerging markets for proper disposal. Each plastic credit represents one tonne of multi-layer plastic. That addresses the first issue – the plastic collection problem.

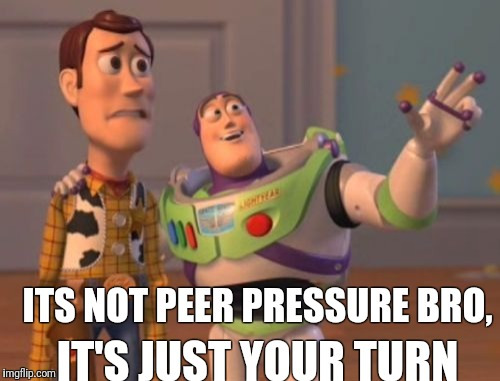

It’s also a great value proposition for consumer brands, especially ones that have built their public image on ideas of wellness, or health, or “natural” ingredients. What’s clever is that Cleanhub has created a whole content hub for their customers that makes it really, really easy for brands to shout about their efforts on social media. And the more Cleanhub’s customers post about what they are doing to reduce their plastic footprint, the more pressure it puts on other brands to do something about it too… hopefully with Cleanhub.

What Cleanhub Wants To Do Tomorrow: An Asset-Light Supply Chain

But let’s talk about the third problem – the issue of an inefficient waste plastic supply chain for recycling. (We’ll get to the second problem in a second.) If you’re a brand telling your customers that you’ve cleaned up a tonne (or three) of plastic waste, you need to be able to stand behind your numbers. So unlike other plastic pollution startups, Cleanhub has chosen to focus on nonrecyclable plastics. Waste collection companies already collect and generate revenue on recyclable plastics – so Cleanhub’s plastic credits represent a truly incremental revenue stream for something that was previously worthless. That additional revenue stream makes waste collection companies much more willing to use Cleanhub’s track-and-trace system to account for the volumes of plastic waste going through their facilities – because that’s the only way they get paid for the nonrecyclable plastic. And as they get used to the operating system and appreciate how intuitive it is and how much more insight they get into their operations, they start to use it to track more than just the plastic that Cleanhub pays for – they start to use it to run their whole business.

At its core, what Cleanhub has built is a plastic accounting platform, with accounting and fraud prevention principles borrowed from fintech to make sure that what’s being captured on Cleanhub’s system is really what is happening on the ground. That data helps subscale waste managers in developing markets to access capital to expand and grow. But additionally, imagine that there are lots of waste managers all over the Global South that use Cleanhub’s systems to account for the waste plastic they collect and trade. All that data is pouring into Cleanhub’s systems – so what you get is a reliable data feed of where plastic waste is originating, the quality of it, the exact households where it came from, and where it is going, at… dare we say… industrial scale. It’s still Shaggy, but with a haircut and a shave.

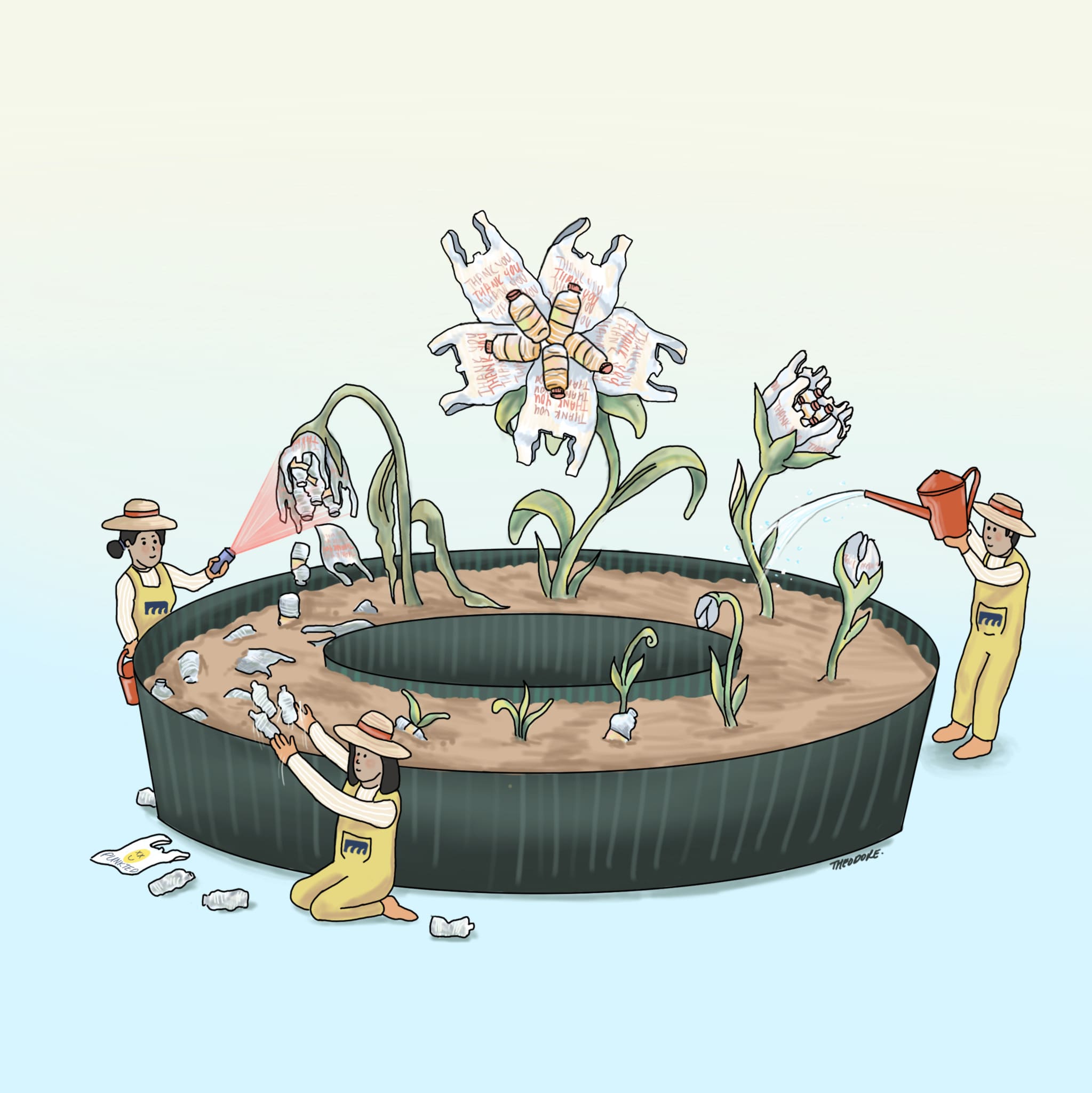

Ultimately, the goal is circular plastic. Something might start life as a disposable razor in someone’s shower, get picked up by a waste collector, pass through a sorting and recycling facility, and end up as part of a shampoo bottle on the supermarket shelf. And you’d be able to track it every step of the way.

Some Important Technology Tailwinds: A Brief Foray into Mechanical vs. Chemical Plastic Recycling

Now to get to the second issue – the fact that not all plastics can be recycled. In that discussion, we were referring to mechanical recycling – where plastics get sorted, shredded into pellets, and then used to make new products. In recent years, interest has been growing in chemical recycling, where plastics get broken down into their base chemicals that can be reconstituted into virgin-grade, food-grade packaging. Chemical recycling has the potential to handle a much wider range of plastics than mechanical recycling can – including those pesky multi-layer plastic snack packets. With a process that breaks plastics down so thoroughly, the ability to track, trace and provide provenance for where the raw material for something came from becomes ever more important – whether that’s to satisfy consumer demand, or legislative action.

And a lot of chemical recycling capacity is coming online. The global installed capacity for chemical recycling was under 2.5 million tonnes as of 2021. But a string of plastics manufacturers have been announcing big investments in the space, including Eastman and Dow. As it comes online, the bottleneck will be the availability of high quality feedstock to provide the scale needed to run chemical recycling facilities – and Cleanhub will be there to provide it.

The Counter Argument: What Could Go Wrong

There are a number of challenges that Cleanhub faces.

First, Cleanhub’s platform is all about making sure that every piece of plastic is accurately tracked and accounted for. But every time software interacts with the real world, the opportunity for inaccuracies accrue – if it can happen in a highly optimised Amazon warehouse, imagine when software is deployed in the messy world of waste management. In order to mitigate this, the company has deployed a range of accounting principles and fraud prevention measures borrowed from fintech, and continues to refine them. It’ll never be perfect – but it’ll keep getting closer.

Second, the solutions to the plastics problem come with their own environmental costs. The best commercially available method to dispose of non-recyclable plastics today is co-processing, which comes with its own carbon footprint. Chemical recycling technology, which will supercharge the demand for waste plastic, is still evolving. Yields are still unproven, and energy requirements are high.

But then again, there is always a tradeoff in the fight against climate change. Electric vehicles, for example, rely on batteries – and batteries come with real environmental downsides. Boyan Slat’s recent article in the NYT had a great quote from the environmental scientist Vaclav Smal – he said that plastic is one of the four “great pillars of modern civilisation.” As Slat wrote, the reality is that we need to prepare for a future where humanity uses more plastic, not less. The better thing to do is find the tradeoff that has the smallest impact on the environment – trade out plastic for alternative materials where possible, reduce and reuse where we can, and then find the most responsible way to deal with what’s left.

Lastly, competition will emerge. The supply and demand imbalance is too large for other people not to notice. Cleanhub already has competitors in the plastic credits space: Plastic Bank in Canada, Plastic Credit Exchange in the Philippines, rePurpose Global in New York. And there are others in adjacent spaces too. Everyone is taking slightly different approaches, but it isn’t a huge stretch to imagine that they’ll all start thinking about ways to address the supply bottleneck. The good news is that this is not a winner-take-all market, and it’s big enough to accommodate multiple players. The ones that will win are the ones that can deliver the highest quality, most reliable volume, and highest degree of trackability. And that’s where Cleanhub comes in ahead of the pack.

Some Final Thoughts

Climate change is a big problem, but many have also lost billions investing in startups that are trying to solve it. Back in November last year, Bessemer Venture Partners wrote an article about the eight lessons we should learn from the first climate tech boom and bust. The most interesting three were:

- Avoid relying exclusively on altruism to scale

- Leverage regulatory environment as tailwind

- Invest in engineering problems, not science experiments

Cleanhub’s business model touches on all three. Cleanhub’s growth comes from the fact that consumers, employees, board members and governments are all pushing industry actors to do something about the plastic pollution problem. It earns its revenue today because brands know that consumers are willing to pay a premium to buy products that are environmentally responsible, but it’ll earn its revenue tomorrow because governments will mandate that brands look for solutions to the recycled plastic shortage. Lastly, while chemical recycling of plastic has some way to go before it is fully commercially viable, it’s getting close, and Cleanhub isn’t betting on any company or any technology getting there first – it just wants to supply the feedstock that will allow a chemical recycling facility to achieve scale.

It’s ludicrous that FMCG brands are scouring supply chains for reliable, high-quality recycled plastic at a reasonable cost – and yet the Pacific Ocean garbage patch just keeps getting bigger. Cleanhub is leading a revolution that will divert plastic from the ocean and divert it into a productive circular resource. Over the last couple centuries, companies have made huge profits extracting resources out of the ground, refining them, and turning them into products. In the coming century, money will be made in making sure that products can get turned back into their raw material components and reconstituted into new products, over and over again.